What does it mean to “square a circle

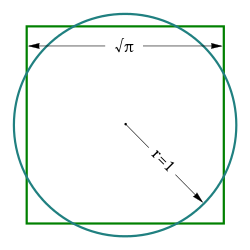

Squaring the circle: the areas of this square and this circle are both equal to π. In 1882, it was proven that this effigy cannot be constructed in a finite number of steps with an idealized compass and straightedge.

Some apparent partial solutions gave false promise for a long fourth dimension. In this effigy, the shaded figure is the Lune of Hippocrates. Its expanse is equal to the area of the triangle ABC (found by Hippocrates of Chios).

Squaring the circumvolve is a problem proposed by ancient geometers. It is the challenge of constructing a square with the same surface area every bit a given circle past using only a finite number of steps with compass and straightedge. The difficulty of the problem raised the question of whether specified axioms of Euclidean geometry concerning the beingness of lines and circles implied the being of such a square.

In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible, every bit a effect of the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem, which proves that pi (π) is a transcendental, rather than an algebraic irrational number; that is, information technology is not the root of any polynomial with rational coefficients. Information technology had been known for decades that the construction would be impossible if π were transcendental, just π was not proven to exist transcendental until 1882. Approximate squaring to any given not-perfect accuracy, in dissimilarity, is possible in a finite number of steps, since there are rational numbers arbitrarily close to π.

The expression "squaring the circle" is sometimes used as a metaphor for trying to exercise the impossible.[1]

The term quadrature of the circle is sometimes used to mean the same thing as squaring the circle, but information technology may also refer to approximate or numerical methods for finding the area of a circle.

History [edit]

Methods to gauge the expanse of a given circumvolve with a square, which can be thought of as a precursor problem to squaring the circle, were known already to Babylonian mathematicians. The Egyptian Rhind papyrus of 1800 BC gives the surface area of a circle every bit 64 / 81 d 2, where d is the diameter of the circle. In modern terms, this is equivalent to approximating π as 256 / 81 (approximately 3.1605), a number that appears in the older Moscow Mathematical Papyrus and is used for book approximations (e.one thousand. hekat). Indian mathematicians too found an approximate method, though less accurate, documented in the Shulba Sutras.[two] Archimedes proved the formula for the area of a circle ( A = π r 2 , where r is the radius of the circle) and showed that the value of π lay between three+ i / 7 (approximately 3.1429) and 3+ 10 / 71 (approximately 3.1408). See Numerical approximations of π for more on the history.

The start known Greek to exist associated with the problem was Anaxagoras, who worked on information technology while in prison. Hippocrates of Chios squared certain lunes, in the promise that it would lead to a solution – see Lune of Hippocrates. Retort the Sophist believed that inscribing regular polygons within a circumvolve and doubling the number of sides will eventually make full up the area of the circle, and since a polygon tin can be squared, it ways the circle tin can be squared. Even then there were skeptics—Eudemus argued that magnitudes cannot be divided up without limit, so the area of the circle will never exist used up.[3] The problem was even mentioned in Aristophanes's play The Birds.

It is believed that Oenopides was the first Greek who required a plane solution (that is, using only a compass and straightedge). James Gregory attempted a proof of its impossibility in Vera Circuli et Hyperbolae Quadratura (The True Squaring of the Circumvolve and of the Hyperbola) in 1667.[four] Although his proof was faulty, it was the first paper to attempt to solve the problem using algebraic backdrop of π. It was non until 1882 that Ferdinand von Lindemann rigorously proved its impossibility.

The Victorian-historic period mathematician, logician, and writer Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, also expressed interest in debunking illogical circumvolve-squaring theories. In 1 of his diary entries for 1855, Dodgson listed books he hoped to write including one called "Plain Facts for Circle-Squarers". In the introduction to "A New Theory of Parallels", Dodgson recounted an attempt to demonstrate logical errors to a couple of circle-squarers, stating:[half-dozen]

The starting time of these two misguided visionaries filled me with a great ambition to do a feat I have never heard of every bit accomplished by human, namely to convince a circumvolve squarer of his fault! The value my friend selected for Pi was 3.2: the enormous fault tempted me with the idea that it could exist hands demonstrated to BE an error. More than a score of letters were interchanged earlier I became sadly convinced that I had no chance.

A ridiculing of circle-squaring appears in Augustus de Morgan's A Budget of Paradoxes published posthumously past his widow in 1872. Having originally published the piece of work equally a series of articles in the Athenæum, he was revising information technology for publication at the time of his death. Circle squaring was very pop in the nineteenth century, only inappreciably anyone indulges in it today and it is believed that de Morgan'southward work helped bring this well-nigh.[vii]

The two other classical bug of antiquity, famed for their impossibility, were doubling the cube and trisecting the angle. Like squaring the circumvolve, these cannot exist solved past compass-and-straightedge methods. All the same, unlike squaring the circumvolve, they tin can be solved by the slightly more powerful construction method of origami, as described at mathematics of paper folding.

Impossibility [edit]

The solution of the problem of squaring the circle by compass and straightedge requires the construction of the number √ π . If √ π is constructible, it follows from standard constructions that π would also be constructible. In 1837, Pierre Wantzel showed that lengths that could be constructed with compass and straightedge had to be solutions of certain polynomial equations with rational coefficients.[viii] [9] Thus, constructible lengths must be algebraic numbers. If the trouble of the quadrature of the circumvolve could exist solved using merely compass and straightedge, then π would have to be an algebraic number. Johann Heinrich Lambert conjectured that π was not algebraic, that is, a transcendental number, in 1761.[10] He did this in the same paper in which he proved its irrationality, even before the general beingness of transcendental numbers had been proven. It was not until 1882 that Ferdinand von Lindemann proved the transcendence of π and and so showed the impossibility of this structure.[11]

The transcendence of π implies the impossibility of exactly "circumvoluted" the square, besides every bit of squaring the circle.

It is possible to construct a square with an area arbitrarily shut to that of a given circle. If a rational number is used as an approximation of π, then squaring the circle becomes possible, depending on the values chosen. Notwithstanding, this is only an approximation and does non run into the constraints of the ancient rules for solving the problem. Several mathematicians have demonstrated workable procedures based on a variety of approximations.

Angle the rules by introducing a supplemental tool, allowing an space number of compass-and-straightedge operations or by performing the operations in certain non-Euclidean geometries besides makes squaring the circumvolve possible in some sense. For example, the quadratrix of Hippias provides the ways to square the circle and also to trisect an arbitrary angle, as does the Archimedean spiral.[12] Although the circle cannot be squared in Euclidean space, it sometimes can be in hyperbolic geometry under suitable interpretations of the terms.[13] [xiv] Every bit in that location are no squares in the hyperbolic aeroplane, their role needs to be taken past regular quadrilaterals, meaning quadrilaterals with all sides congruent and all angles coinciding (simply these angles are strictly smaller than correct angles). There be, in the hyperbolic aeroplane, (countably) infinitely many pairs of constructible circles and constructible regular quadrilaterals of equal surface area, which, still, are constructed simultaneously. There is no method for starting with a regular quadrilateral and constructing the circle of equal surface area, and there is no method for starting with a circle and constructing a regular quadrilateral of equal area (even when the circle has small enough radius such that a regular quadrilateral of equal area exists).

Modernistic approximative constructions [edit]

Though squaring the circle with perfect accurateness is an impossible trouble using only compass and straightedge, approximations to squaring the circle can be given by constructing lengths close toπ. It takes but minimal knowledge of simple geometry to convert any given rational approximation of π into a corresponding compass-and-straightedge construction, but constructions made in this way tend to be very long-winded in comparison to the accuracy they achieve. Afterwards the exact problem was proven unsolvable, some mathematicians applied their ingenuity to finding elegant approximations to squaring the circumvolve, defined roughly and informally as constructions that are particularly simple among other imaginable constructions that give similar precision.

Construction by Kochański [edit]

One of the early on historical approximations is Kochański's approximation which diverges from π simply in the 5th decimal place. It was very precise for the time of its discovery (1685).[fifteen]

Construction co-ordinate to Kochański with continuation

In the left diagram

Construction by Jacob de Gelder [edit]

Jacob de Gelder'due south construction with continuation

In 1849 an elegant and simple construction past Jacob de Gelder (1765-1848) was published in Grünert'southward Archiv. That was 64 years earlier than the comparable construction by Ramanujan.[sixteen] It is based on the approximation

This value is authentic to six decimal places and has been known in China since the 5th century as Zu Chongzhi's fraction, and in Europe since the 17th century.

Gelder did not construct the side of the square; it was plenty for him to discover the following value

- .

The illustration opposite – described below – shows the construction past Jacob de Gelder with continuation.

Describe 2 mutually perpendicular center lines of a circle with radius CD = ane and decide the intersection points A and B. Lay the line segment CE = fixed and connect Due east to A. Determine on AE and from A the line segment AF = . Draw FG parallel to CD and connect Due east with G. Describe FH parallel to EG, and then AH = Determine BJ = CB and subsequently JK = AH. Halve AK in L and use the Thales'due south theorem effectually 50 from A, which results in the intersection point M. The line segment BM is the square root of AK and thus the side length of the searched square with near the same area.

Examples to illustrate the errors:

- In a circumvolve of radius r = 100 km, the mistake of side length a ≈ seven.5 mm

- In the instance of a circle with radius r = 1 m, the error of the area A ≈ 0.3 mmii

Structure past Hobson [edit]

Amongst the modern approximate constructions was one past E. West. Hobson in 1913.[16] This was a fairly accurate construction which was based on constructing the judge value of 3.14164079..., which is accurate to three decimal places (i.e. it differs from π by about 4.8×10−5 ).

Hobson's construction with continuation

-

- "We find that GH = r . 1 . 77246 ..., and since = i . 77245 we see that GH is greater than the side of the foursquare whose area is equal to that of the circle by less than two hundred thousandths of the radius."

Hobson does not mention the formula for the approximation of π in his construction. The above illustration shows Hobson's structure with continuation.

Constructions by Ramanujan [edit]

The Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan in 1913,[17] [18] Carl Olds in 1963, Martin Gardner in 1966, and Benjamin Bold in 1982 all gave geometric constructions for

which is accurate to six decimal places ofπ.

Ramanujan's judge construction with the approach

355 / 113

DR is the side of the square

Sketch of "Manuscript book 1 of Srinivasa Ramanujan" p. 54

In 1914, Ramanujan gave a ruler-and-compass construction which was equivalent to taking the approximate value for π to exist

giving eight decimal places of π.[xix] He describes his construction till line segment OS every bit follows.[xx]

"Allow AB (Fig.2) be a diameter of a circumvolve whose centre is O. Bisect the arc ACB at C and trisect AO at T. Bring together BC and cut off from it CM and MN equal to AT. Join AM and AN and cut off from the latter AP equal to AM. Through P draw PQ parallel to MN and meeting AM at Q. Join OQ and through T draw TR, parallel to OQ and meeting AQ at R. Draw Every bit perpendicular to AO and equal to AR, and bring together Bone. Then the hateful proportional between Os and OB will be very almost equal to a sixth of the circumference, the error being less than a 12th of an inch when the diameter is 8000 miles long."

In this quadrature, Ramanujan did not construct the side length of the square, information technology was plenty for him to show the line segment OS. In the following continuation of the structure, the line segment OS is used together with the line segment OB to represent the hateful proportionals (ruby line segment OE).

Squaring the circle, guess structure according to Ramanujan of 1914, with continuation of the construction (dashed lines, mean proportional red line), run into animation.

Continuation of the construction up to the desired side length a of the square:

Extend AB beyond A and beat the round arc b1 around O with radius OS, resulting in S′. Bisect the line segment BS′ in D and describe the semicircle b2 over D. Describe a directly line from O through C upwardly to the semicircle btwo, it cuts b2 in E. The line segment OE is the mean proportional between OS′ and OB, besides chosen geometric mean. Extend the line segment EO beyond O and transfer EO twice more, it results F and Aone, and thus the length of the line segment EA1 with the above described approximation value of π, the half circumference of the circle. Bisect the line segment EA1 in G and depict the semicircle b3 over G. Transfer the distance OB from A1 to the line segment EA1 , it results H. Create a vertical from H upwardly to the semicircle b3 on EA1 , information technology results B1. Connect Ai to B1, thus the sought side a of the square AiBiCiD1 is constructed, which has most the aforementioned expanse as the given circle.

Examples to illustrate the errors:

- In a circle of radius r = 10,000 km the error of side length a ≈ −ii.8 mm

- In the example of a circle with the radius r = 10 m the error of the area A ≈ −0.i mm2

Construction using the golden ratio [edit]

- In 1991, Robert Dixon gave a construction for where is the golden ratio.[21] Three decimal places are equal to those of π.

- If the radius and the side of the square and then the expanded second formula shows the sequence of the steps for an alternative structure (meet the following analogy). 4 decimal places are equal to those of √ π .

Estimate construction using the golden ratio

.

Squaring or quadrature as integration [edit]

Finding the area under a bend, known as integration in calculus, or quadrature in numerical analysis, was known equally squaring earlier the invention of calculus. Since the techniques of calculus were unknown, information technology was more often than not presumed that a squaring should be done via geometric constructions, that is, by compass and straightedge. For case, Newton wrote to Oldenburg in 1676 "I believe Grand. Leibnitz will not dislike the Theorem towards the beginning of my letter pag. 4 for squaring Curve lines Geometrically" (emphasis added).[22] Subsequently Newton and Leibniz invented calculus, they yet referred to this integration problem as squaring a curve.

Claims of circumvolve squaring [edit]

Connection with the longitude problem [edit]

The mathematical proof that the quadrature of the circle is impossible using merely compass and straightedge has not proved to exist a hindrance to the many people who have invested years in this problem anyhow. Having squared the circle is a famous crank assertion. (See besides pseudomathematics.) In his old age, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes convinced himself that he had succeeded in squaring the circle, a claim that was refuted by John Wallis as role of the Hobbes–Wallis controversy.[23] [24]

During the 18th and 19th century, the notion that the problem of squaring the circle was somehow related to the longitude problem seems to accept become prevalent among would-be circumvolve squarers. Using "cyclometer" for circle-squarer, Augustus de Morgan wrote in 1872:

Montucla says, speaking of France, that he finds three notions prevalent among cyclometers: 1. That at that place is a large advantage offered for success; 2. That the longitude problem depends on that success; iii. That the solution is the great end and object of geometry. The same 3 notions are as prevalent amongst the aforementioned grade in England. No reward has always been offered by the government of either country.[25]

Although from 1714 to 1828 the British government did indeed sponsor a £xx,000 prize for finding a solution to the longitude problem, exactly why the connectedness was fabricated to squaring the circumvolve is not articulate; specially since two non-geometric methods (the astronomical method of lunar distances and the mechanical chronometer) had been found past the late 1760s. The Lath of Longitude received many proposals, including determining longitude by "squaring the circle", though the lath did non take "any find" of information technology.[26] De Morgan goes on to say that "[t]he longitude trouble in no manner depends upon perfect solution; existing approximations are sufficient to a point of accuracy far across what can exist wanted." In his book, de Morgan also mentions receiving many threatening letters from would-be circle squarers, accusing him of trying to "cheat them out of their prize".

Other modernistic claims [edit]

Even after it had been proved incommunicable, in 1894, amateur mathematician Edwin J. Goodwin claimed that he had developed a method to square the circle. The technique he developed did not accurately square the circle, and provided an wrong area of the circle which essentially redefined pi as equal to 3.2. Goodwin so proposed the Indiana Pi Bill in the Indiana state legislature allowing the state to use his method in education without paying royalties to him. The bill passed with no objections in the country house, but the nib was tabled and never voted on in the Senate, among increasing ridicule from the press.[27]

The mathematical crank Carl Theodore Heisel also claimed to accept squared the circle in his 1934 book, "Behold! : the thou problem no longer unsolved: the circle squared beyond refutation."[28] Paul Halmos referred to the book as a "classic crank book."[29]

In 1851, John Parker published a volume Quadrature of the Circle in which he claimed to have squared the circle. His method really produced an approximation of π accurate to half-dozen digits.[30] [31] [32]

In literature [edit]

J. P. de Faurè, Dissertation, découverte, et demonstrations de la quadrature mathematique du cercle, 1747

The problem of squaring the circle has been mentioned by poets such equally Dante and Alexander Pope, with varied metaphorical meanings. Its literary utilize dates dorsum at least to 414 BC, when the play The Birds by Aristophanes was outset performed. In it, the character Meton of Athens mentions squaring the circle, peradventure to betoken the paradoxical nature of his utopian city.[33]

Dante's Paradise, canto XXXIII, lines 133–135, contain the verses:

As the geometer his heed applies

To square the circle, nor for all his wit

Finds the right formula, howe'er he tries

For Dante, squaring the circle represents a job beyond human comprehension, which he compares to his own inability to comprehend Paradise.[34]

Past 1742, when Alexander Pope published the fourth book of his Dunciad, attempts at circle-squaring had come up to be seen as "wild and fruitless":[31]

Mad Mathesis alone was unconfined,

Also mad for mere material chains to bind,

At present to pure space lifts her ecstatic stare,

Now, running round the circle, finds it square.

Similarly, the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera Princess Ida features a vocal which satirically lists the impossible goals of the women's university run by the title character, such as finding perpetual motility. One of these goals is "And the circle – they will foursquare information technology/Some fine 24-hour interval."[35]

The sestina, a poetic class first used in the twelfth century past Arnaut Daniel, has been said to square the circle in its use of a square number of lines (half dozen stanzas of six lines each) with a circular scheme of six repeated words. Spanos (1978) writes that this form invokes a symbolic meaning in which the circle stands for heaven and the foursquare stands for the world.[36] A similar metaphor was used in "Squaring the Circle", a 1908 brusk story past O. Henry, nigh a long-running family feud. In the championship of this story, the circle represents the natural globe, while the square represents the city, the world of homo.[37]

In later on works circle-squarers such as Leopold Bloom in James Joyce'southward novel Ulysses and Lawyer Paravant in Thomas Isle of mann's The Magic Mountain are seen every bit sadly deluded or as unworldly dreamers, unaware of its mathematical impossibility and making grandiose plans for a upshot they will never attain.[38] [39]

See too [edit]

- For a more modern related problem, see Tarski's circumvolve-squaring trouble.

- The squircle is a mathematical shape with backdrop between those of a square and those of a circle.

References [edit]

- ^ Ammer, Christine. "Square the Circumvolve. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of Idioms". Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved sixteen Apr 2012.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. & Robertson, Edmund F. (2000). "The Indian Sulbasutras". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. St Andrews University.

- ^ Heath, Thomas (1981). History of Greek Mathematics . Courier Dover Publications. ISBN0-486-24074-6.

- ^ Gregory, James (1667). Vera Circuli et Hyperbolæ Quadratura … [The true squaring of the circle and of the hyperbola …]. Padua: Giacomo Cadorino. Bachelor at: ETH Bibliothek (Zürich, Switzerland)

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1919). A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). New York: The Macmillan Visitor. p. 143.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1996). The Universe in a Handkerchief . Springer. ISBN0-387-94673-Ten.

- ^ Dudley, Underwood (1987). A Budget of Trisections. Springer-Verlag. pp. xi–xii. ISBN0-387-96568-8. Reprinted as The Trisectors.

- ^ Wantzel, L. (1837). "Recherches sur les moyens de reconnaître si un problème de géométrie peut se résoudre avec la règle et le compas" [Investigations into means of knowing if a problem of geometry can exist solved with a straightedge and compass]. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées (in French). 2: 366–372.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1918). "Pierre Laurent Wantzel". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 24 (7): 339–347. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1918-03088-seven. MR 1560082.

- ^ Lambert, Johann Heinrich (1761). "Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendentes circulaires et logarithmiques" [Memoir on some remarkable properties of circular transcendental and logarithmic quantities]. Histoire de fifty'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres de Berlin (in French) (published 1768). 17: 265–322.

- ^ Lindemann, F. (1882). "Über die Zahl π" [On the number π]. Mathematische Annalen (in German). 20: 213–225. doi:ten.1007/bf01446522. S2CID 120469397.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B.; Merzbach, Uta C. (11 January 2011). A History of Mathematics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-0-470-52548-7. OCLC 839010064.

- ^ Jagy, William C. (1995). "Squaring circles in the hyperbolic aeroplane" (PDF). Mathematical Intelligencer. 17 (ii): 31–36. doi:10.1007/BF03024895. S2CID 120481094.

- ^ Greenberg, Marvin Jay (2008). Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries (Fourth ed.). W H Freeman. pp. 520–528. ISBN978-0-7167-9948-1.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Kochanski's Approximation". MathWorld.

- ^ a b Hobson, Ernest William (1913). Squaring the Circle: A History of the Problem. Cambridge University Printing. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Wolfram, Stephen. "Who Was Ramanujan?". See too MANUSCRIPT Book i OF SRINIVASA RAMANUJAN page 54 Both files were retrieved at 23 June 2016

- ^ Castellanos, Dario (April 1988). "The Ubiquitous π". Mathematics Magazine. 61 (2): 67–98. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1988.11977350. ISSN 0025-570X.

- ^ South. A. Ramanujan: Modular Equations and Approximations to π In: Quarterly Journal of Mathematics. 12. Another curious approximation to π is, 43, (1914), S. 350–372. Listed in: Published works of Srinivasa Ramanujan

- ^ S. A. Ramanujan: Modular Equations and Approximations to π In: Quarterly Periodical of Mathematics. 12. Some other curious approximation to π is ... Fig. ii, 44, (1914), Due south. 350–372. Listed in: Published works of Srinivasa Ramanujan

- ^ Dixon, Robert A. (ane January 1991). Mathographics. Courier Corporation. ISBN978-0-486-26639-8. OCLC 22505850.

- ^ Cotes, Roger (1850). Correspondence of Sir Isaac Newton and Professor Cotes: Including letters of other eminent men.

- ^ Boyd, Andrew (2008). "HOBBES AND WALLIS". Episode 2372. The Engines of Our Ingenuity. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Bird, Alexander (1996). "Squaring the Circle: Hobbes on Philosophy and Geometry". Journal of the History of Ideas. 57 (2): 217–231. doi:10.1353/jhi.1996.0012. S2CID 171077338.

- ^ de Morgan, Augustus (1872). A Budget of Paradoxes. p. 96.

- ^ Board of Longitude / Vol V / Confirmed Minutes. Cambridge Academy Library: Royal Observatory. 1737–1779. p. 48. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Numberphile (12 March 2013), How Pi was about changed to 3.2 - Numberphile

- ^ Heisel, Carl Theodore (1934). Behold! : the grand problem the circle squared beyond refutation no longer unsolved. Heisel.

- ^ Paul R. Halmos (1970). "How to Write Mathematics". L'Enseignement mathématique. 16 (2): 123–152. — Pdf

- ^ Beckmann, Petr (2015). A History of Pi. St. Martin's Press. p. 178. ISBN9781466887169.

- ^ a b Schepler, Herman C. (1950). "The chronology of pi". Mathematics Magazine. 23 (iii): 165–170, 216–228, 279–283. doi:10.2307/3029284. JSTOR 3029832. MR 0037596.

- ^ Abeles, Francine F. (1993). "Charles L. Dodgson's geometric approach to arctangent relations for pi". Historia Mathematica. 20 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1006/hmat.1993.1013. MR 1221681.

- ^ Amati, Matthew (2010). "Meton'south star-metropolis: Geometry and utopia in Aristophanes' Birds". The Classical Journal. 105 (3): 213–222. doi:10.5184/classicalj.105.three.213. JSTOR x.5184/classicalj.105.iii.213.

- ^ Herzman, Ronald B.; Towsley, Gary B. (1994). "Squaring the circle: Paradiso 33 and the poetics of geometry". Traditio. 49: 95–125. doi:10.1017/S0362152900013015. JSTOR 27831895.

- ^ Dolid, William A. (1980). "Vivie Warren and the Tripos". The Shaw Review. 23 (two): 52–56. JSTOR 40682600. Dolid contrasts Vivie Warren, a fictional female mathematics pupil in Mrs. Warren's Profession past George Bernard Shaw, with the satire of college women presented by Gilbert and Sullivan. He writes that "Vivie naturally knew improve than to effort to square circles."

- ^ Spanos, Margaret (1978). "The Sestina: An Exploration of the Dynamics of Poetic Structure". Speculum. 53 (3): 545–557. doi:10.2307/2855144. JSTOR 2855144. S2CID 162823092.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1987). Twentieth-century American literature. Chelsea Business firm Publishers. p. 1848. ISBN9780877548034.

Similarly, the story "Squaring the Circle" is permeated with the integrating paradigm: nature is a circle, the city a foursquare.

- ^ Pendrick, Gerard (1994). "2 notes on "Ulysses"". James Joyce Quarterly. 32 (1): 105–107. JSTOR 25473619.

- ^ Goggin, Joyce (1997). The Big Deal: Card Games in 20th-Century Fiction (PhD). University of Montréal. p. 196.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Squaring the circle at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Squaring the circle at Wikimedia Eatables

- Squaring the circle at the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- Squaring the Circumvolve at cut-the-knot

- Circle Squaring at MathWorld, includes information on procedures based on various approximations of pi

- "Squaring the Circle" at "Convergence"

- The Quadrature of the Circle and Hippocrates' Lunes at Convergence

- How to Unroll a Circle Pi accurate to 8 decimal places, using straightedge and compass.

- Squaring the Circumvolve and Other Impossibilities, lecture by Robin Wilson, at Gresham College, 16 January 2008 (available for download every bit text, audio or video file).

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Motorcar: Grime, James. "Squaring the Circle". Numberphile. Brady Haran.

- "2000 years unsolved: Why is doubling cubes and squaring circles impossible?" by Burkard Polster

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squaring_the_circle

![{\displaystyle \left(9^{2}+{\frac {19^{2}}{22}}\right)^{\frac {1}{4}}={\sqrt[{4}]{\frac {2143}{22}}}=3.141\;592\;65{\color {red}2\;582\;\ldots }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b19708cac1c9e05a4970d69955f3722a6ef12e2f)

0 Response to "What does it mean to “square a circle"

Post a Comment